The Dadaist’s Inevitability

The Dadaist’s Inevitability

Beatrice Vandenberghe

Abstract

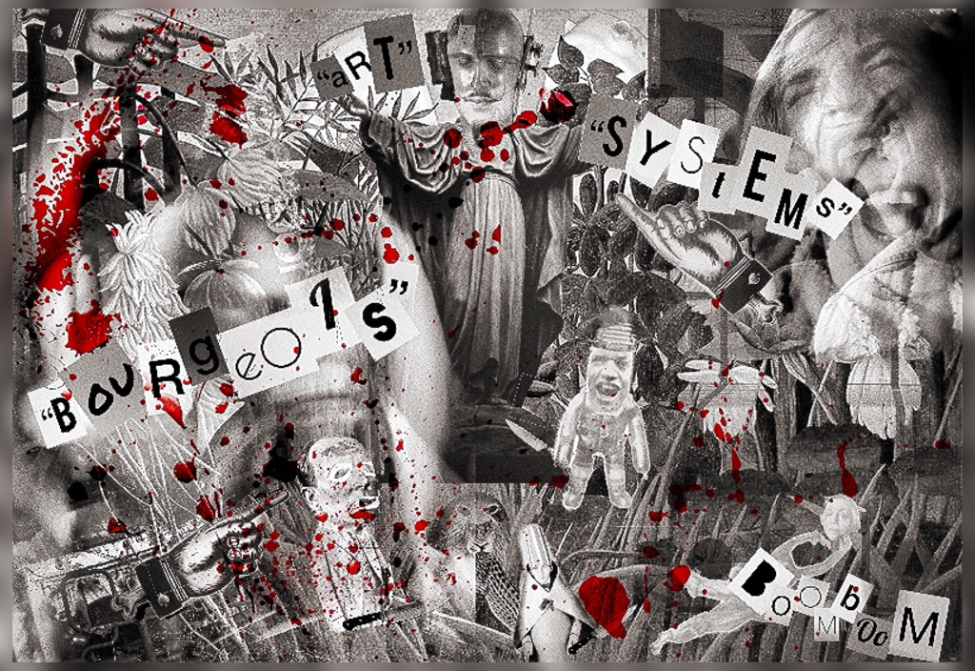

The Dadaist’s Inevitability is a visual art piece that depicts Dadaism’s medium of photomontage through digital technology. It webs together various influential Dadaist pieces with contemporary photography and bitmap images to create a multimedia piece that might be described as dark, grisly, or macabre. The art piece, together with its written reflection, calls into question the strength and viability of Dadaism’s central philosophies as they are expressed through Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto 1918”.

Fig. 1. The Dadaist's Inevitability. Digital artwork by Beatrice Vandenberghe, 2024.

As an art movement, Dadaism encourages chaos, nonsense, and irrationality; as a moral philosophy, Dadaism protests capitalism and the privileged existence of the bourgeois. It is idealistic, innovative, and experimental in its tenets, and it is absolutely impractical.

Dadaism was an invaluable tool for fighting the arduous circumstances from which it was born. The movement was a response to tremendous suffering inflicted upon splintered peoples and with its genesis and continuance came great political activism. In this essay, I call attention to its flaws and caution against revolutionary ideals that may cause harms in their own right.

In designing my visual artwork, I wanted to dialogue with the central principles of Dadaism by incorporating the aesthetic of photomontage, an art form inherent to the Dada movement as a means of vocalization, a means of protest against the suffering inflicted upon individuals by the First World War. In photomontage there is a surreal, skewed, fragmented objectivity that screams to challenge the status quo. Elements of notable Dadaist works are included. It was within my inspiration to depict a society that has emerged as a consequence of Dadaist ideals: that is, a systemless world that resides in a state of perpetual anarchy. It is meant to be unpleasant and bleak and violent.

The concept is based on Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto 1918,” in which he outlines Dadaism’s most fundamental ideas, including its inherent and purposeful absurdity:

I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestoes, as I am also against principles (half-pints to measure the moral value of every phrase too too convenient; approximation was invented by the impressionists). I write this manifesto to show that people can perform contrary actions together while taking one fresh gulp of air; I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense. (Tzara)

While Tzara writes that he does not make any statement, his text spans many pages making broad statements. And while the Dadaist may not have an objective when engaging with their movement, their principles, were they to be actualized, will still result in a discernible outcome. And while, in the faithful Dadaist, there is a strong distaste for societal systems, a coherently proposed alternative to such systems is non-existent. Inevitably, then, the Dadaist’s world based on nonsense and chaos will be nonsensical and chaotic.

This picture of anarchy is conveniently delivered through the Dadaist’s own medium of photomontage. In making my work, I compiled works from influential Dada artists such as Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann and laid them against the backdrop of Henri Rousseau’s The Repast of the Lion. Rousseau’s work with post-impressionist primitivism is both aesthetically applicable and hints to the ironic accompanying Western philosophy that argues for the favourable state of ethics interlaid within Urgesellschaft (“primordial society”). In doing this, I argue that it is inevitable that the Dadaist’s world will be deranged and violent.

Indeed, the movement satirizes systems such as capitalism partially due to their tendency toward exploitation, and their subsequent production of inequities and violence. However, it is likely that these problems will continue to thrive, if only in a different form, with the removal of systems. This seems to present a problem for Tzara given his resentment towards the violence perpetuated by systems. It might be that it is only systemic violence that is the issue—to me, the question of whether the origin of violence is systemic or anti-systemic is less relevant than the eventual, indistinguishable consequence. And to this point, the Dadaist might respond with, “that’s fine, it is irrelevant, and it is meant to be nonsense anyway. It’s what we’ve been saying all along.” I take issue with this. By shrugging off all forms of reason and logic, the movement becomes infallible to all arguments against it, which, ironically, is one of the tactics employed by one of the most authoritative systems in human history: religion. Despite Dada’s clear distaste towards religion (which is generously referenced throughout the whole of Tzara’s text, for example, “The attempt of Jesus and the Bible covers with their broad benevolent wings: shit, animals, days”), the phenomenon of infallibility seems to be a relevant corollary between the two systems of thought. It’s also a little ironic that Tzara’s manifesto comes off as quite preachy, stating that “Morality creates atrophy,” that it is “an injection of chocolate into the veins of all men,” while also expressing a very deeply felt rage, disgust and dissatisfaction with the immorality currently set in place by corrupt systems. I doubt that the text would be so demonstrably angry were it to be legitimate in expressing a disinterest in morals. For these reasons, religious symbolism is present in the creative work. Tzara, as a key Dadaist, claims to want, say, and do nothing while committing to all the above with the fervour of a missionary.

It is also relevant to note that, among the text presented in the creative work that reference the most important themes of Dadaism, (e.g., “bourgeois,” “art,” and “boomboom”), “Dada” is not one of them. This is meant to reflect the idea that Dada as a philosophy is self-defeating—it would fail to exist were its ideals to come to fruition. With a philosophy based on nonsense and chaos, it follows that society would regress so far into primordial drives that Dadaism as a concept would be impossible. In this way, the Dadaist’s ideal—at least as it is described through Tzara’s text—is a hellscape that refuses to recall its own origin and intention.

Works Cited

Ajayan, Sanjay. “White Van in Forest During Daytime.” Unsplash, 23 Jan. 2020, unsplash.com/photos/white-van-in-forest-during-daytime-OVJK_HewiB0.

Ball, Hugo. “Reciting the Sound Poem ‘Karawane.’” 1916. photograph. Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. The Art Story, https://www.theartstory.org/ movement/dada/.

Duchamp, Marcel. Fountain. 1917. glazed ceramic with black paint. San Franscisco Museum of Modern Art; Purchase through a gift of Phyllis Wattis, San Francisco, United States. Artstor, https://jstor.org/stable/community.14704405.

---. L.H.O.O.Q. 1919. rectified readymade: pencil on postcard reproduction. Minneapolis College of Art and Design, Minneapolis, United States. Artstor, https://jstor.org/stable/community.14396916.

Eric. “Knife PNG File PNG Mart.” PNG Mart, 3 Feb. 2017, www.pngmart.com/files/3/Knife-PNG-File.

Fuller, Joshua. “Woman in White and Black Stripe Long Sleeve Shirt.” Unsplash, 19 Oct. 2020, unsplash.com/photos/woman-in-white-and-black-stripe-long-sleeve-shirt-_I5DYcYuo6c.

Hausmann, Raoul. Der Geist Unserer Zeit – Mechanischer Kopf (Spirit of the Age: Mechanical Head). 1919. mixed media assemblage. Musee National D’Art Moderne (Centre Pompidou), Paris, France. Artstor, https://jstor.org/stable/ community.18112601.

---. The Art Critic. 1919-1920. lithograph and printed paper on paper. Tate, https:// www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hausmann-the-art-critic-t01918.

Höch, Hannah. Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany). 1919. photomontage. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany. Artstor, https:// jstor.org/stable/community.18128838.

Nevozhai, Denys. “White Building.” Unsplash, 26 Oct. 2019, unsplash.com/photos/white-building-HoSHJ7KCZdQ.

A personal touch. www.tripadvisor.ca/Attraction_Review-g189158-d12920370-Reviews-Lisbon_with_Pats-Lisbon_Lisbon_District_Central_Portugal.html#/media-atf/12920370/360120589:p/?albumid=-160&type=0&category=-160.

Rey, Arturo. “Grayscale Photograph of Jesus Christ Statue.” Unsplash, 16 Apr. 2018, unsplash.com/photos/grayscale-photograph-of-jesus-christ-statue-CvnVk7GGQCg.

Rojal. “Blood PNG Transparent Images - PNG All.” PNG All, 23 Mar. 2018, www.pngall.com/blood-png.

Rousseau, Henri. The Repast of the Lion. 1907. oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States. Artstor, https://jstor.org/stable/ community.16004441.

Skelton, Callum. “Grayscale Photo of Man in Suit.” Unsplash, 22 Nov. 2018, unsplash.com/photos/grayscale-photo-of-man-in-suit-LaMnXPLz7qc.

Tzara, Tristan. “Dada Manifesto [1918].” The Dada Painters and Poets, translated by Robert Motherwell. 2nd ed., The Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1981, pp. 76–82.

Beatrice Vandenberghe is an undergraduate student at the University of British Columbia.

Picture: “The Dadaist’s Inevitability.” Original digital artwork by Beatrice Vandenberghe.